Key Takeaways

- Standardized tests don’t accurately measure student learning and growth.

- Unlike standardized tests, performance-based assessment allows students to choose how they show learning.

- Performance-based assessment is equitable, accurate, and engaging for students and teachers.

Break out your No. 2 pencil and answer this multiple choice question: How do standardized tests measure student learning?

If you didn’t answer “all of the above,” then: A. You haven’t been paying attention, or B. You work for a testing software company.

Most of us know that standardized tests are inaccurate, inequitable, and often ineffective at gauging what students actually know. The good news is, there’s a better way: Performance-based assessment provides an essential piece of the puzzle in measuring student growth.

What is Performance-Based Assessment (PBA)?

This system of learning and assessment allows students to demonstrate knowledge and skill through critical-thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and the application of knowledge to real-world situations. In other words, it helps students prepare for college, career, and life.

PBA also allows educators to create more engaging instruction and address learning gaps by observing over time. And it helps them gather well-rounded information to better support their students’ success—a far cry from the “drill and kill” of state and federal standardized tests.

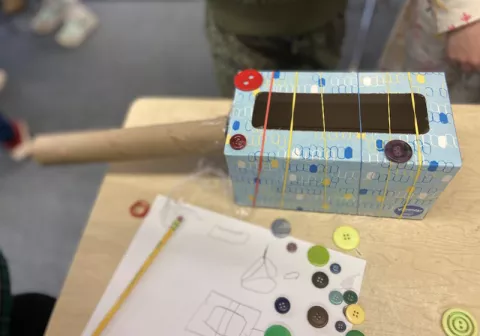

PBA can mean asking students to compose a few sentences in an open-ended short response; develop a thorough analysis in an essay; conduct a laboratory investigation; curate a portfolio of student work; or complete an original research paper.

Younger students may design experiments, write poems, or create art that demonstrate concepts.

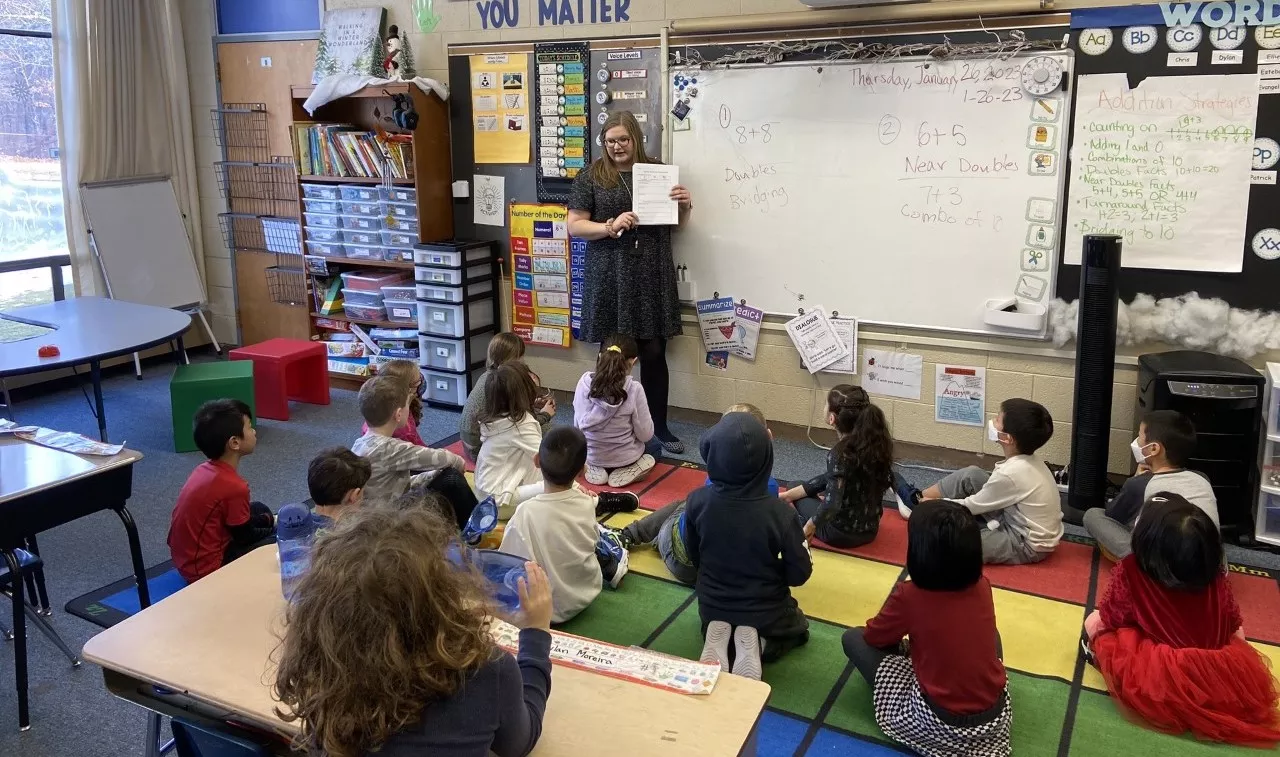

“PBA allows students more choice in how they can show what hey’ve learned, and it allows differentiated instruction for different learning styles,” says Molly Malinowski, a first-grade teacher at Lynch Elementary School, in the Winchester school district, in Massachusetts. “Standardized tests don’t allow choice because it’s one-size-fits-all. Students may have the knowledge, but may not be able to show what they know and understand on the test. They can demonstrate that in PBA.”

Built-in Differentiation

One of Malinowski’s favorite math assessments focuses on addition, using numbers from 0 through 20. She introduces the concept and, with inquiry-based instruction, presents lessons and talks about strategies. As students pose questions or problems, the process ignites their curiosity. At the end of the unit, they have an “addition celebration.”

She starts by building fluency and then asks students to share their problem-solving strategies with the class.

“The best part is that they get to show their learning in a lot of different ways,” Malinowski says. “For this math standard, they make a video, a poster, a voice recording, a mini-play, or a piece of writing. Students have a voice in how they demonstrate their learning.”

PBA allows students to demonstrate knowledge and skill through critical-thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and the application of knowledge to real-world situations. In other words, it helps students prepare for college, career, and life.

And when they share with the class, that helps reinforces everyone’s learning, she explains. None of this is possible in an individual test.

“With this kind of instruction and assessment, we can … offer targeted support,” she says. “Some students will want to create their own piece of work, while others need more scaffolding, so I can really see who is learning what.”

Each academic area in her school, from math to language arts to science and social studies, has a PBA.

“We’ve been encouraged to take time to develop PBAs for our grade level, developing and tweaking them, and trying them out and making edits as we go,” she adds.

Sequences, Not Snapshots

Malinowski teaches in one of eight public school districts participating in the Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment (MCIEA).

MCIEA is a partnership between these school districts and their local teachers unions, who are working together to create a fair and effective accountability system, offering a more dynamic picture of student quality and learning than a single standardized test.

“The first objective of MCIEA is to measure student learning in a way that relies on teacher-created, classroom-embedded, performance assessments rather than externally created standardized assessments,” says MCIEA co-founder Jack Schneider. “The second objective is to measure school quality in a way that is more holistic, valid, and democratic than standardized tests.”

The consortium’s framework goes beyond test scores and graduation and absentee rates, instead focusing on multiple measures of student engagement and achievement, as well as school environment.

“It’s a more equitable system that doesn’t punish marginalized students,” Schneider explains.

The current data used to measure student success, adds Schneider, closely correlates to race, income, and family educational attainment. It really only tells us about advantage and disadvantage outside school, not what schools are actually doing.

“We want to capture all of the things that show student learning and achievement, not just this tortuously narrow vision that is embedded in the current system,” he says.

“Where in the data is student engagement, their sense of belonging, performing arts, or development of civic competencies?” he asks. “There are massive gaps. So many of the current variables are just demographics in disguise.”

On a standardized test, there is only one right answer. Every other answer is wrong. But educators know when students are engaged in authentic and meaningful tasks, they can arrive at answers that are not entirely wrong or entirely right.

“We’d never give someone a standardized test to see if they can fly an airplane,” Schneider says. “PBA can show us much more effectively what a student knows that actually reflects the complexity of knowing and doing something.”

Leveling the Playing the Field

Alissa Holland is an instructional coach in the Milford Public Schools district, in Massachusetts, one of the districts participating in the MCIEA.

“Standardized tests create test anxiety and some kids even have test phobia because they have just this one chance at getting it right,” says Holland, who works at Stacy Middle School. “PBA allows students to ask more questions and bounce ideas around, which reduces anxiety without reducing rigor."

PBA also removes bias and creates more equity. For example, Holland recalls a state standardized test question about decomposition for eighth-grade science: “The question asked about grass clippings after mowing the lawn, and students got hung up on ‘grass clippings,’” she says. “Some had no idea what they were because they either lived in apartments and had no lawns, or they had lawns but didn’t mow them because they had landscapers.”

A PBA on decomposition, on the other hand, would allow students to show their learning by demonstrating it with something they’re familiar with—grass clippings, an apple core, or leaves in the park—in a diagram, an essay or poem, or artwork. Students can show much more of their knowledge over time, in a form they choose, rather than on one day, on one test question, where only one answer is right, Holland explains.

“Working on a PBA shows growth while inspiring a growth mindset,” Holland says.

Her colleague Dan Cote, a social studies teacher in the same district, agrees. Nobody likes to regurgitate everything they know on a single test, he says.

“The PBA process acknowledges that learning happens in different stages, where we can give feedback and build skills during the assessment,” Cote says. “It also increases engagement because students walk in the shoes of a geographer or historian, with tasks that mimic real world activities.”

Stronger Relationships with Students

Standards and rubrics don’t always call for collaboration, and there’s certainly no teamwork on a test, but in PBA, students often work in groups that build critical social skills.

When Cote’s students learn about earlier civilizations, they form teams of four and decide together what time period and landscape their civilization would inhabit.

“They have tough decisions to make and problems to solve, like laws for farmers, how to respond to a natural disaster, what they should invest in as a civilization,” Cote explains.

“Then each student writes their version of what happened, like a historian would—which demonstrates how easily bias occurs when the students read the other students’ varying versions of the same events.”

Then the students create artifacts from their civilizations, and their classmates try to guess which civilization each student inhabited.

At the end of every PBA, Cote debriefs with the class.

“Students always say that working together was the best part,” he says. That’s the best part for the teachers, too, because it helps them build stronger relationships with students.

“We gain so much more when we can hear their thoughts,” Cote says. “It’s not about a gotcha on a test score.”