Key Takeaways

- Since their inception a century ago, standardized tests have been instruments of racism and a biased system.

- Students of color, particularly those from low-income families, have suffered the most from high-stakes testing in U.S. public schools.

- Today, a movement is growing across the country to resist testing abuse and overuse, and to promote authentic assessment.

As many students return to in-person learning for the first time in almost a year, states and school districts are also beginning to gear up for statewide standardized testing, as required by the US Department of Education (ED).

In April 2020, as the pandemic engulfed the nation and forced schools to close, the department granted a “blanket waiver” to every state to skip mandated statewide testing for 2019-20. Last month, however, ED officials announced it was mandating schools to administer some form of statewide assessment for 2020-21.

Educators across the country criticized the decision, saying the idea that students should be forced to take any sort of standardized test this year is incomprehensible. The priority right now should be on strengthening instruction and support for students and families in communities most traumatized by the impact of the coronavirus.

Many of these same communities have suffered the most from high-stakes testing. Since their inception almost a century ago, the tests have been instruments of racism and a biased system. Decades of research demonstrate that Black, Latin(o/a/x), and Native students, as well as students from some Asian groups, experience bias from standardized tests administered from early childhood through college.

"We still think there’s something wrong with the kids rather than recognizing their something wrong with the tests," Ibram X. Kendi of the Antiracist Research & Policy Center at Boston University and author of How to be an Antiracist said in October 2020. "Standardized tests have become the most effective racist weapon ever devised to objectively degrade Black and Brown minds and legally exclude their bodies from prestigious schools."

Yet some organizations insist on more testing, arguing that the data will expose the gaps where support and resources should be directed.

Standardized tests, however, have never been accurate and reliable measures of student learning.

“While much has been said about the racial achievement gap as a civil rights issue, more attention needs to be paid to the measurement tools used to define that gap,” explains Young Wan Choi, manager of performance assessments for the Oakland Unified school District in Oakland, CA. “Education reformists, civil rights organizations, and all who are concerned with racial justice in education need to advocate for assessment tools that don’t replicate racial and economic inequality.”

Testing Pioneer – and Eugenicist

"To tell the truth about standardized tests," Kendi said, "is to tell the story of the eugenicists who created and popularized these tests in the United States more than a century ago."

As the U.S. absorbed millions of immigrants from Europe beginning in the 19th century, the day’s leading social scientists, many of them White Anglo-Saxon Protestants, were concerned by the infiltration of non-whites into the nation’s public schools.

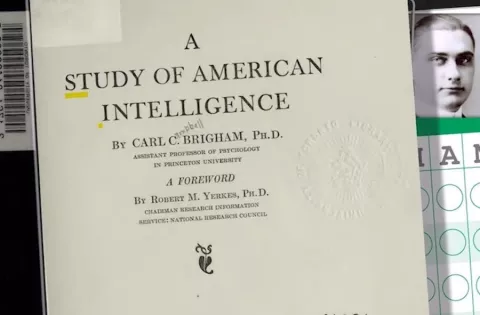

In his 1923 book, A Study of American Intelligence, psychologist and eugenicist Carl Brigham wrote that African-Americans were on the low end of the racial, ethnic, and/or cultural spectrum. Testing, he believed, showed the superiority of “the Nordic race group” and warned of the “promiscuous intermingling” of new immigrants in the American gene pool.

Furthermore, the education system he argued was in decline and "will proceed with an accelerating rate as the racial mixture becomes more and more extensive."

Brigham had helped to develop aptitude tests for the U.S. Army during World War I and – commissioned by the College Board - was influential in the development of the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT). At the time, he and other social scientists considered the SAT a new psychological test and a supplement to existing college board exams.

The SAT debuted in 1926, joined by the ACT (American College Testing) in the 1950s. By the 21st century, the SAT and ACT were just part of a barrage of tests students may face before reaching college. The College Board also offers SAT II tests, designed for individual subjects ranging from biology to geography.

Entrenched in Schools

Brigham’s Ph.D. dissertation, written in 1916, “Variable Factors in the Binet Tests,” analyzed the work of the French psychologist Alfred Binet, who developed intelligence tests as diagnostic tools to detect learning disabilities. The Stanford psychologist Lewis Terman relied on Binet’s work to produce today’s standard IQ test, the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Tests.

During World War I, standardized tests helped place 1.5 million soldiers in units segregated by race and by test scores. The tests were scientific yet they remained deeply biased, according to researchers and media reports.

In 1917, Terman and a group of colleagues were recruited by the American Psychological Association to help the Army develop group intelligence tests and a group intelligence scale. Army testing during World War I ignited the most rapid expansion of the school testing movement.

By 1918, there were more than 100 standardized tests, developed by different researchers to measure achievement in the principal elementary and secondary school subjects. The U.S. Bureau of Education reported in 1925 that intelligence and achievement tests were increasingly used to classify students at all levels.

The first SAT was administered in 1926 to more than 8,000 students, 40 percent of them female. The original test lasted 90 minutes and consisted of 315 questions focused on vocabulary and basic math.

“Unlike the college boards, the SAT is designed primarily to assess aptitude for learning rather than mastery of subjects already learned,” according to Erik Jacobsen, a New Jersey writer and math-physics teacher based at Newark Academy in Livingston, N.J. “For some college officials, an aptitude test, which is presumed to measure intelligence, is appealing since at this time (1926) intelligence and ethnic origin are thought to be connected, and therefore the results of such a test could be used to limit the admissions of particularly undesirable ethnicities.”

By 1930, multiple-choice tests were firmly entrenched in U.S. schools. The rapid spread of the SAT sparked debate along two lines. Some critics viewed the multiple-choice format as encouraging memorization and guessing. Others examined the content of the questions and reached the conclusion that the tests were racist.

Eventually, Brigham adapted the Army test for use in college admissions, and his work began to interest interested administrators at Harvard University. Starting in 1934, Harvard adopted the SAT to select scholarship recipients at the school. Many institutions of higher learning soon followed suit.

The Triumph of Pseudo-Science

In his essay “The Racist Origins of the SAT,” Gil Troy calls Brigham a “Pilgrim-pedigreed, eugenics-blinded bigot.” Eugenics is often defined as the science of improving a human population by controlled breeding to increase the occurrence of desirable heritable characteristics. It was developed by Francis Galton as a method of improving the human race. Only after the perversion of its doctrines by the Nazis in World War II was the theory dismissed.

“All-American decency and idealism coexisted uncomfortably with these scientists’ equally American racism and closemindedness,” Troy writes.

Binet, Terman, and Brigham stood at the intersection of powerful intellectual, ideological, and political trends a century ago when the Age of Science and standardization began, according to Troy.

“In (those) consensus-seeking times, scientists became obsessed with deviations and handicaps, both physical and intellectual,” Troy states. “And many social scientists, misapplying Charles Darwin’s evolving evolutionary science, and eugenics’ pseudo-science, worried about maintaining white purity.”

Decades of Racial Bias

By the 1950s and 1960s, top U.S. universities were talent-searching for the “brainy kids,” regardless of ethnicity, states Jerome Karabel in “The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton.”

This dictum among universities to identify the brightest students as reflected by test scores did not bode well for students from communities of color, who were—as a result of widespread bias in testing—disproportionately failing state or local high school graduation exams, according to the National Center for Fair and Open Testing (FairTest).

According to Fair Test, on average, students of color score lower on college admissions tests, thus many capable youth are denied entrance or access to so-called “merit” scholarships, contributing to the huge racial gap in college enrollments and completion.

High-stakes testing also causes additional damage to some students who are categorized as English language learners (ELLs). The tests are often inaccurate for ELLs, according to FairTest, leading to misplacement or retention. ELLs are, alongside students with disabilities, those least likely to pass graduation tests.

African-Americans, especially males, are disproportionately placed or misplaced in special education, frequently based on test results. In effect, the use of high-stakes testing perpetuates racial inequality through the emotional and psychological power of the tests over the test takers.:

And although most test makers screen test items for obvious bias, their efforts often do not detect underlying bias in the test’s form or content.

These biases have long-ranging and damaging consequences not only for students, their families but also the economic well-being of their communities.

There is a clear correlation, for example, between test scores and property values.

Popular private school ratings systems such as GreatSchools.org (40 million unique visitors every year) may be accelerating existing patterns of racial and socioeconomic segregation. Their rankings are based largely on standardized test scores and are fed into national real estate web sites. According to a 2019 study of GreatSchools ratings, areas with highly-rated schools usually see increases in home prices.

"Affluent and more educated families were better positioned to leverage this new information to capture educational opportunities in communities with the best schools," the authors wrote. "An unintended consequence of better information was less, rather than more, equity in education."

A Chalkbeat analysis found that GreatSchools ratings effectively penalize schools that serve low-income and Black and Hispanic students, “generally giving them significantly lower ratings than schools serving more affluent and more white and Asian students."

More Effective Assessment Systems

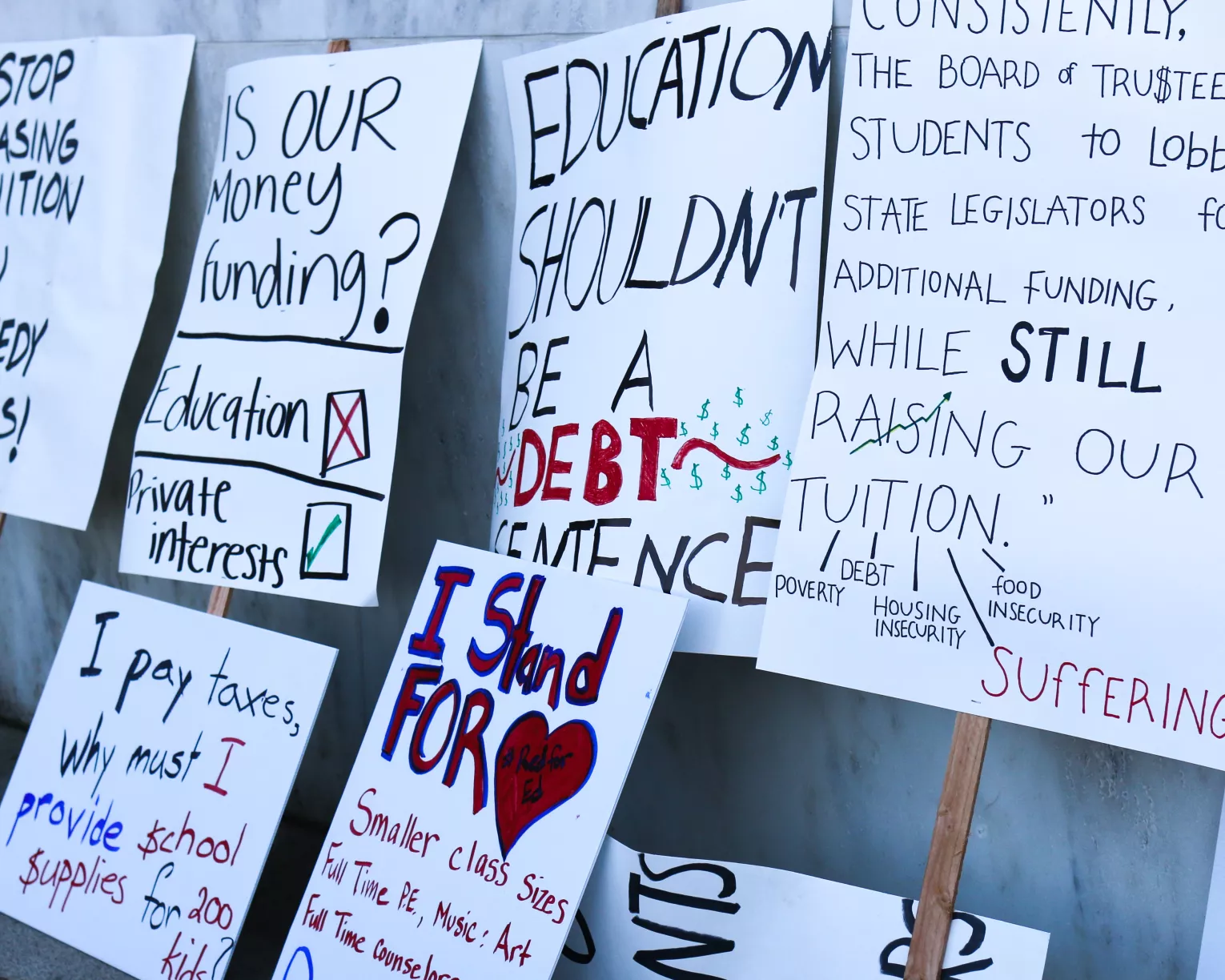

The National Education Association believes that the guidance offered by the Department of Education in February doesn’t go far enough in providing the necessary flexibility schools need to support their students. Moving forward, the focus should be on promoting authentic assessments that reflect the broad range of students learning and skills, including creativity, leadership, critical thinking, and collaboration.

This was a conversation that drove many of the educator-led victories in the years before the pandemic. Joining forces with families and other allies, educators worked diligently to reduce the over-reliance and misuse of testing and shift the focus to fairer, more effective assessment systems that actually support the academic, social and emotional needs of their students.

Suggested Further Reading

-

Dismantling White Supremacy Includes Ending Racist Tests like the SAT and ACT

Teachers College Press

-

A Secret Strategy to Keep Out Black Students

The Atlantic

-

The Racist and Classist Roots of Standardized Testing Found a Home at Stanford University They Still Endure Today

The Stanford Daily

-

A Civil Rights Challenge to Standardized Testing in College Admissions

Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Libertes Law Review

-

The Gathering Resistance to Standardized Tests

Rethinking Schools

Active anywhere decisions impact our students.

From the School Board to the Statehouse or even the White House, OEA members make our collective voice heard on a host of issues that impact our students, educators, and communities.

Learn more about what we're doing to improve the lives of our students, educators, and families.